Political religions and fascism

The creation of new symbols and rituals to evoke belief in a higher cause are central to the concept, ‘political religion’, prevalent in fascism studies for at least two decades.

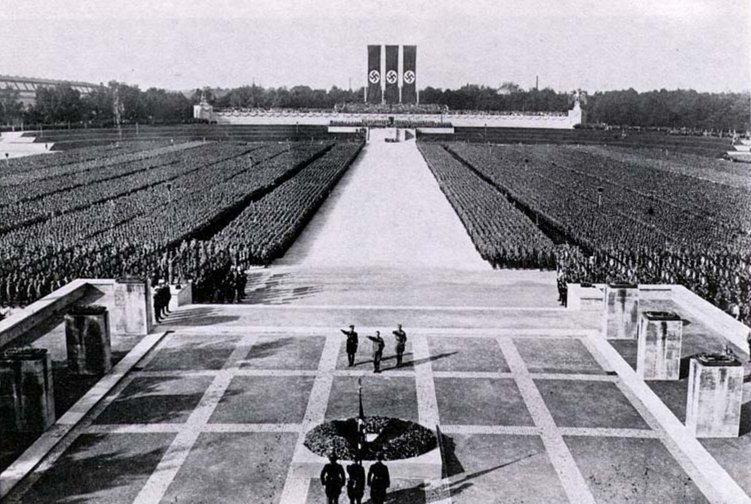

‘I'm beginning to comprehend, I think, some of the reasons for Hitler’s astounding success. Borrowing a chapter from the Roman church, he is restoring pageantry and colour and mysticism to the drab lives of twentieth-century Germans.’ So wrote William Shirer in his famous Berlin Diary, commenting on the Nuremberg Rally of 1934.

He continued: ‘This morning’s opening meeting in the Luitpold Hall on the outskirts of Nuremberg was more than a gorgeous show; it also had something of the mysticism and religious fervour of an Easter or Christmas Mass in a great Gothic cathedral.’ Shirer went on to describe how the packed hall was electrified when the band played the Badenweiler March, music only used for Hitler’s entrances. As Hitler arrived, along with other leading Nazis, he was met by saluting followers. Kleig lamps were used to dazzle the stage where he then sat, surrounded by a hundred party officials and army and navy officers. As the music died down, Rudolf Hess read out the names of Nazi ‘martyrs’, those who had died fighting for the movement, while behind the assembled men was the ‘blood flag’ that had been paraded in the streets of Munich on the day of the failed putsch of 1923.

As Shirer concluded, ‘In such an atmosphere no wonder, then, that every word dropped by Hitler seemed like an inspired Word from on high. Man’s – or at least the German’s – critical faculty is swept away at such moments, and every lie pronounced is accepted as high truth itself.’

This powerful scene from the early days of the Third Reich makes us consider how faith and politics are blurred by fascism. The creation of new symbols and rituals to evoke belief in a higher cause are central to the critical concept familiar to many historians of fascism and communism, ‘political religion’. This term has been prevalent in fascism studies for at least two decades, and has a much longer history rooted in contemporary responses to interwar fascism itself.

We’ve got a newsletter for everyone

Whatever you’re interested in, there’s a free openDemocracy newsletter for you.

For its modern advocates, especially Emilio Gentile, political religion explains how fascism was more than a top-down form of domination, and drew out genuine belief from wide sectors of society that lived under fascist regimes or were attracted to fascist movements. The term has also found new relevance for those thinking about the ways evocations of faith in something higher is important for understanding extreme ideologies and regimes. In recent times, the political religion concept has been used to examine a diverse range of more contemporary phenomena,from ISIS to the Christian Identity movement, as well as American neo-Nazi organisations such as the National Alliance, and it has even been used to characterise the ideology of Juche in North Korea.

The sacralisation of politics

One of the first to use the term political religion was a German-American professor of political science. In 1938, just before the Anschluss, Eric Voegelin, an academic based at the University of Vienna and a man appalled by the expansion of Nazism, wrote an essay called The Political Religions. Presenting analysis that stretched from the Egyptian pharaoh Akhenaton to the fascist and communist regimes that had developed since the end of the First World War, Voegelin warned how faith was being manipulated by modern dictatorships, fascist and communist. These new systems were appropriating elements of Christianity’s symbolism to create new types of collective affinity, based either on national identity and race or class. For him, this modern development was rooted in the breakdown of religious faith set in train by the Reformation and then the Enlightenment. Voegelin was a critic of secularisation, and so argued that modern political religions were the logical result of the decadence that the breakdown of traditional notions of faith represented.

Other thinkers of this period were also interested in the political religion concept. In 1939, the French philosopher Raymond Aron warned of ‘notre époque de religions politiques’. During the Second World War he described how communist and fascist totalitarian states tried to develop a type of absolute certainty that was offered by pre-modern Christianity. Yet for Aron they ultimately failed to achieve their aim of unifying society through a new faith as their ideologies were crude, simplistic and a mere caricature of earlier forms of religion. Aron explained in his book L’homme contre le tyrans that the power of Nazism lay in its ability to unite the rationality of modern bureaucratic systems with the power of the irrational through new symbols, mythology and rituals. The era of totalitarian regimes was defined by cynical leaders who manipulated the masses through a modern form of collective fanaticism, Aron concluded.

Interest in the political religion concept from Voegelin, Aron and others from this period, such as Rudolf Rocker, showed that a range of thinkers and writers of the interwar era recognised something quite profound in the ways totalitarian regimes manipulated faith to offer new answers to a world seemingly gone awry. Another was Waldamar Gurain, who by the 1950s went further than Aron and argued that political religions were more than cynical manipulations; rather, they expressed genuinely held beliefs of the leading proponents of these systems. ‘The totalitarian movements which have arisen since World War I are fundamentally religious movements’, Gurain stated in his 1952 essay Totalitarian Religions, adding: ‘The totalitarian political religions are expressions of secularist thought in a world where the inherited traditional stability and continuity are threatened or have disappeared.’ Totalitarian states, in their quest to reshape man and society as a whole, were different from anything that came before. They were based on a new conception of faith that emerged in response to secularised modernity and political crisis.

Building on these earlier thinkers, Emilio Gentile has become the most prominent advocate of the concept in recent times. His key book The Sacralisation of Politics in Fascist Italy, published in English translation in 1996, examined the emotional appeal of Mussolini’s regime. Gentile’s subsequent book, Politics as Religion, then explained in greater conceptual detail his reworking of earlier debates on the relationship between political religions, totalitarianism and secularisation.

Utopian vision

Gentile’s approach argues that political religions are distinct from the broader phenomenon of civil religions, though both are ‘secular religions’. These relatively new developments are also different from the older ‘traditional religions’, such as Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Civil religions remain widespread in secular modernity, and they allow degrees of political sacralisation to sit alongside many other institutions. American patriotism from the late eighteenth century onwards, for example, has been expressed through sacralised phenomena, such as new national symbols, the ritualised worship of the flag and belief in a national mission, yet America has also allowed individual freedoms to flourish and political pluralism to mature. For Gentile, this provides a good working example of a civil religion.

However, Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, as well as the Soviet Union, were exemplars of its more hard-line variant, political religion. Such states, at least in principle, rejected pluralism and instead sought a monopoly on belief and the total commitment from those who lived within them. For Gentile, there are several key features that characterise a political religion. They are founded around a sacralised ideal of an essentially secular identity. Some political religions, such as fascist ones, are based on national identity and race; others, like communism, are based on class. Though ideas of race, nation and class are radically different, for Gentile they could all be used to evoke a sense of a collective identity deemed to be superior to the individual, and so people are morally obliged to carry out what was best for the collective, not themselves. Political religions are diametrically opposed to liberal notions of individualism, in other words.

There is also a utopian vision at the core of a political religion, giving them a sense of messianic mission, binding leaders and followers together in a shared project. Finally, to express this, they develop new rituals that make a leading individual the personification of the political religion’s mission, and a wider mythology that allows societies to engage in activities that express their collective belief in the sacred cause espoused by the new faith.

For comparativists like Gentile, the point is not to reduce all such examples to a single concept, but rather to use the term to develop a deeper understanding of the diverse forms political religions can take. For historians of fascism, it helps explain that fascisms are complex, and not simply a set of prejudices imposed on the masses. People living in interwar fascist regimes, or attracted to fascist movements, were not brainwashed. The faith held by leaders and wider society was symbiotic: many were true believers and were engaged in an ‘anthropological revolution’, an ongoing experiment to create a new type of society.

While Gentile has been at the forefront of defining the concept, others have also come round to his perspective. One leading figure in fascism studies whose own work has always been concerned with the ways myth lies at the core of the appeal of fascism, Roger Griffin, was initially sceptical of the idea of political religion. However, he has become a staunch defender of Gentile’s work, and the concept of political religions more generally.

Others reviving the term in more recent times include Phillipe Burrin, whose 1997 article Political Religion: The Relevance of a Concept critiqued Voegelin, but argued the term was crucial for understanding Nazism and Italian Fascism. Michael Burleigh was another leading advocate of the term by the late 1990s, and a cofounder of the journal Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions, now Politics Religion & Ideology. His books Earthly Powers and Sacred Causes have offered a more popular history approach to exploring the concept. More recently, A. James Gregor’s Totalitarians and Political Religion: An Intellectual History explores the concept from Hegel to National Socialism. It has been applied to cultural figures too, as Matthew Feldman has used the term to help explore the poet and fascist propagandist Ezra Pound.

Reformulations of faith in a secular world

Other modern promoters of the concept are more ambiguous in their embrace of the term. Hans Maier, for example, has edited a three-volume set of books looking at the relationship between totalitarianism and political religion. However, in an article from 2007, he also stated that ‘the concept of “political religions” is, for the time being, a necessary if somewhat ill-defined conceptual category’, adding the term helps us remember that ‘religion does not allow itself to be easily banished from society, and that, where this is tried, it returns in unpredictable and perverted forms.’

David Roberts’s 2009 article ‘Political Religion’ and the Totalitarian Departures of Interwar Europe takes a similar position, acknowledging many problems with the concept while also seeing its value in allowing for a complex reinterpretation of totalitarianism and its history. More forcefully, Ian Kershaw has dismissed the term as ‘voguish’, yet at the same time discussed the importance of understanding Nazism’s ‘pseudo-religious’ qualities, such as its redemptive mission.

Kevin Passmore has levied a more fundamental critique. Drawing on a gender history perspective, he stresses that the origins of the term are rooted in a milieu that prioritised the study of men within fascist movements. For Passmore, recent theorists of political religion have often failed to move beyond fascism’s own gender assumptions, and have marginalised the role of women and their motivations for participating in fascist movements and regimes. He concludes that approaches to studying fascism that do more to break down the distinctions between leaders and followers, elite and masses, are needed to capture the complexity of the gendered dynamics of fascist politics. Moreover, he rather pointedly notes the prominence of male theorists leading the debates regarding the value of the term.

While those wishing to find new applications for the political religion concept would do well to heed warnings from its critics, they could also try to develop it using more recent approaches to history, such as the history of emotions. More work using the political religions concept is timely and necessary, and can stimulate fresh thinking on how diverse forms of political religion allowed deeply held faiths to emerge not only within totalitarian states but also within much more marginalised extremist movements. It allows researchers to frame questions about the levels to which people genuinely believed in fascist politics, past and present, or were manipulated by cynical leaders. It can also offer an approach for comparing fascism with communism and newer extreme movements, such as ISIS. The political religion concept allows us to see that, while radically different, these are all extreme reformulations of faith for a secularising world.

Visit the Centre for Analysis of the Radical Right (#CARR)

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.